You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Article | 02 March 2022 | Investments

The upsetting scenes in Ukraine have sent shockwaves through us all as individuals, and through global stock markets.

However, as tensions soar, investors should try avoid making rash decisions in the heat of the moment. Below are five pieces of data and analysis which I hope can help you do just that.

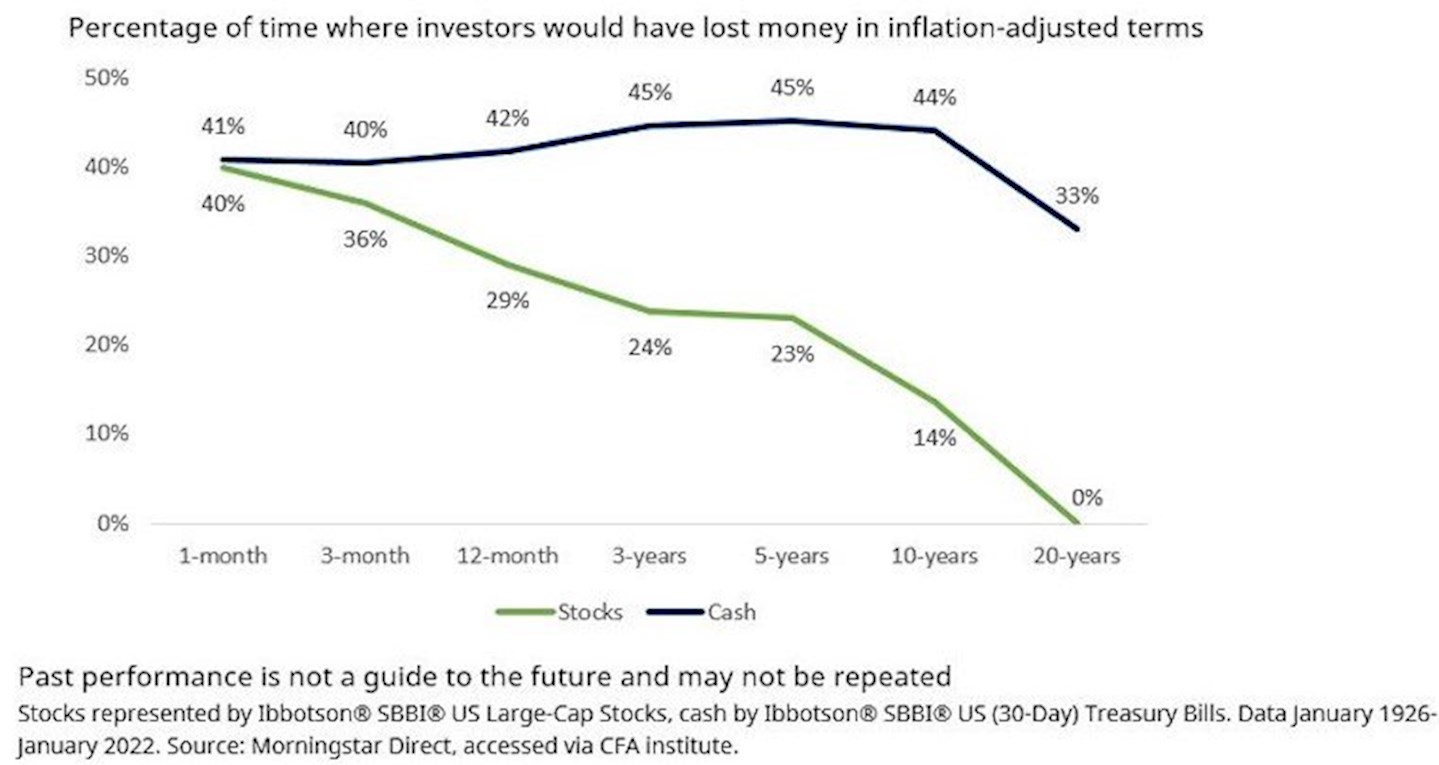

Using almost 100 years of data on the US stock market, we found that, if you invested for a month, you would have lost money 40% of the time in inflation-adjusted terms i.e. in 460 of the 1,153 months in our analysis.

However, if you had invested for longer, the odds would shift dramatically in your favour. On a 12-month basis, you would have lost money slightly less than 30% of the time. Importantly, 12-months is still the short-run when it comes to the stock market. You’ve got to be in it for longer.

On a five-year horizon, that figure falls to 23%. At 10 years it is 14%. And there have been no 20-year periods in our analysis when stocks lost money in inflation-adjusted terms.

Losing money over the long run can never be ruled out entirely and would clearly be very painful if it happened to you. However, it is also a very rare occurrence.

In contrast, while cash may seem safer, the chances of its value being eroded by inflation are much higher. And, as all cash savers know, recent experience has been even more painful. The last time cash beat inflation in any five-year period was February 2006 to February 2011, a distant memory. Nor is that something that’s expected to change any time soon.

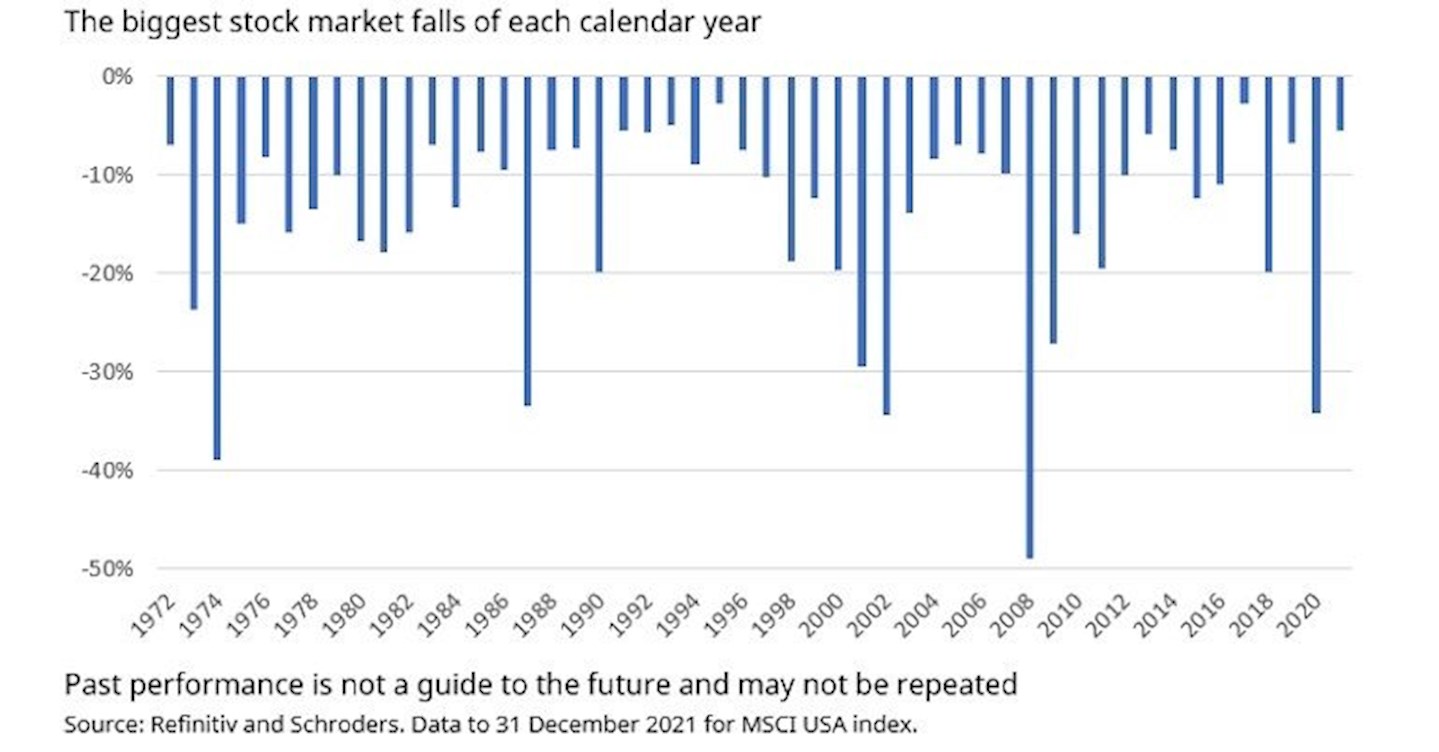

By Thursday of last week, global stock markets had fallen by 10% from their peak. They rebounded on Friday but are heading lower again early this week.

10% may feel like a big fall but it’s actually a regular occurrence. The US market has fallen by at least 10% in 28 of the past 50 calendar years i.e. more often than not. In the past decade, this includes 2012, 2015, 2016, 2018 and 2020.

Despite these regular bumps along the way, the US market has returned 11% a year over this 50 year period overall.

The risk of near term loss is the price of the entry ticket for the long term gains that stock market investing can deliver.

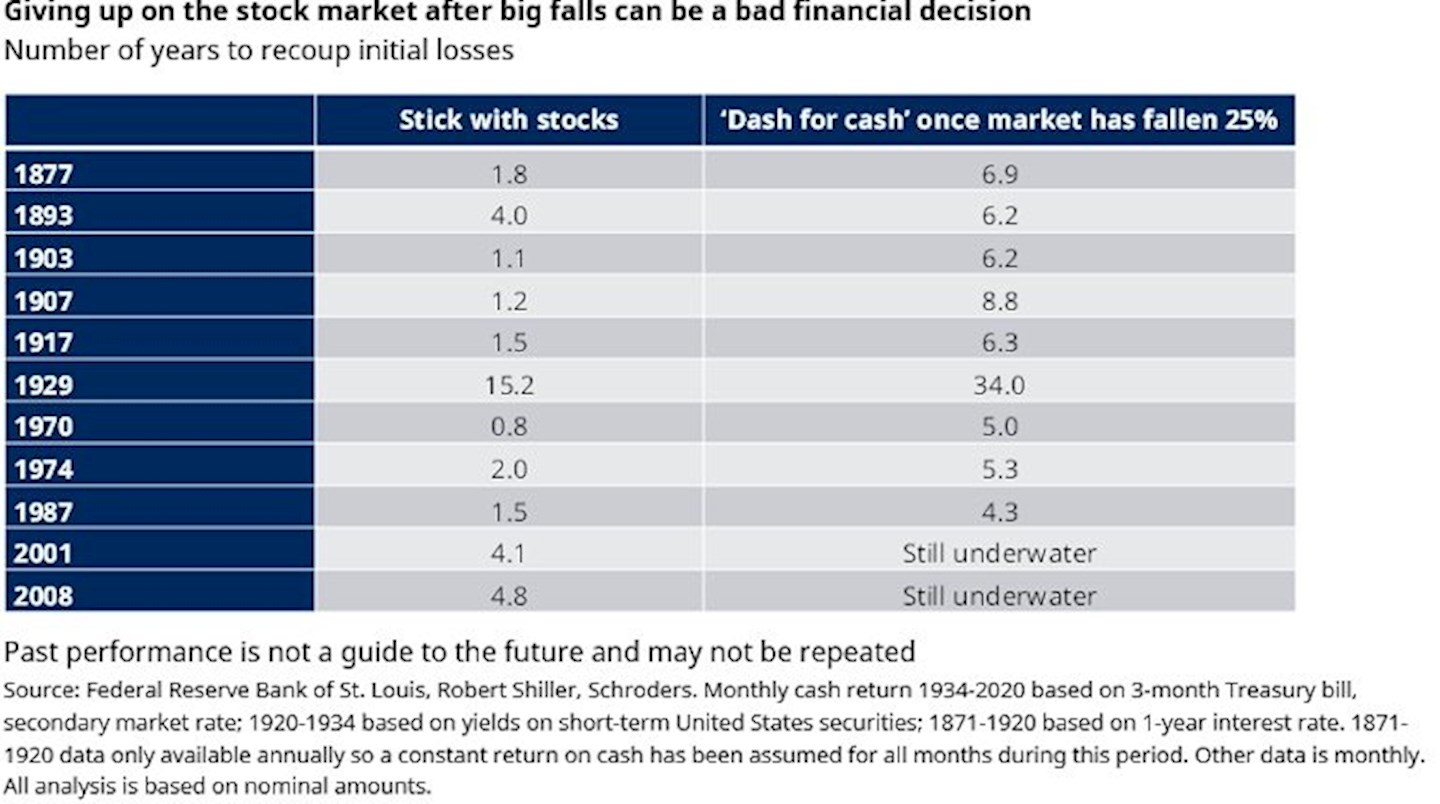

While the market hasn’t fallen too much so far, further volatility and risk of declines cannot be ruled out. If that happens, it can become much harder to avoid being influenced by our emotions – and be tempted to ditch stocks and dash for cash

However, our research shows that, historically, that would have been the worst financial decision an investor could have made. It pretty much guarantees that it would take a very long time to recoup losses.

For example, investors who shifted to cash in 1929, after the first 25% fall of the Great Depression, would have had to wait until 1963 to get back to breakeven. This compares with breakeven in early 1945 if they had remained invested in the stock market. And remember, the stock market ultimately fell over 80% during this crash.

So, shifting to cash might have avoided the worst of those losses during the crash, but still came out as by far the worst long-term strategy.

Similarly, an investor who shifted to cash in 2001, after the first 25% of losses in the dotcom crash, would find their portfolio still underwater today.

The message is overwhelmingly clear: a rejection of the stock market in favour of cash in response to a big market fall would have been very bad for wealth over the long run.

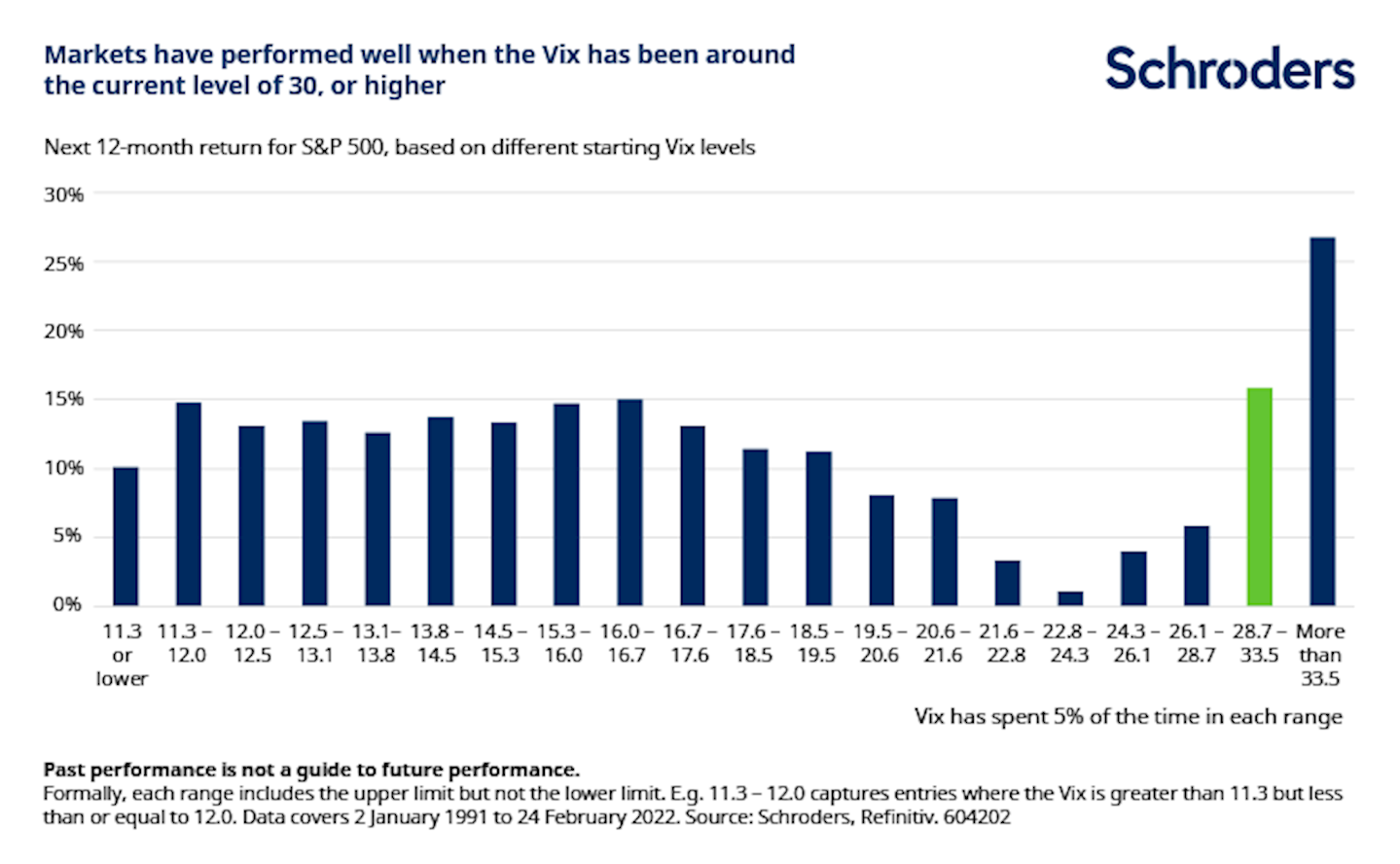

Escalating tensions between Russia and Ukraine have recently sent the stock market’s “fear gauge”, the Vix index, higher. The Vix is a measure of the amount of volatility traders expect for the US’ S&P 500 index during the next 30 days.

It has recently risen to a level of 32 on Monday 28 February, well above its average since 1990 of 19, and steeply higher than its start of year level of 17. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where it moves even higher in the coming days as events continue to unfold.

However, rather than being a time to sell, historically, periods of heightened fear have been when the brave-hearted have earned the best returns. On average, the S&P 500 has generated an average 12-month return of over 15% if the Vix was between 28.7 and 33.5. And more than 26% if it breached 33.5.

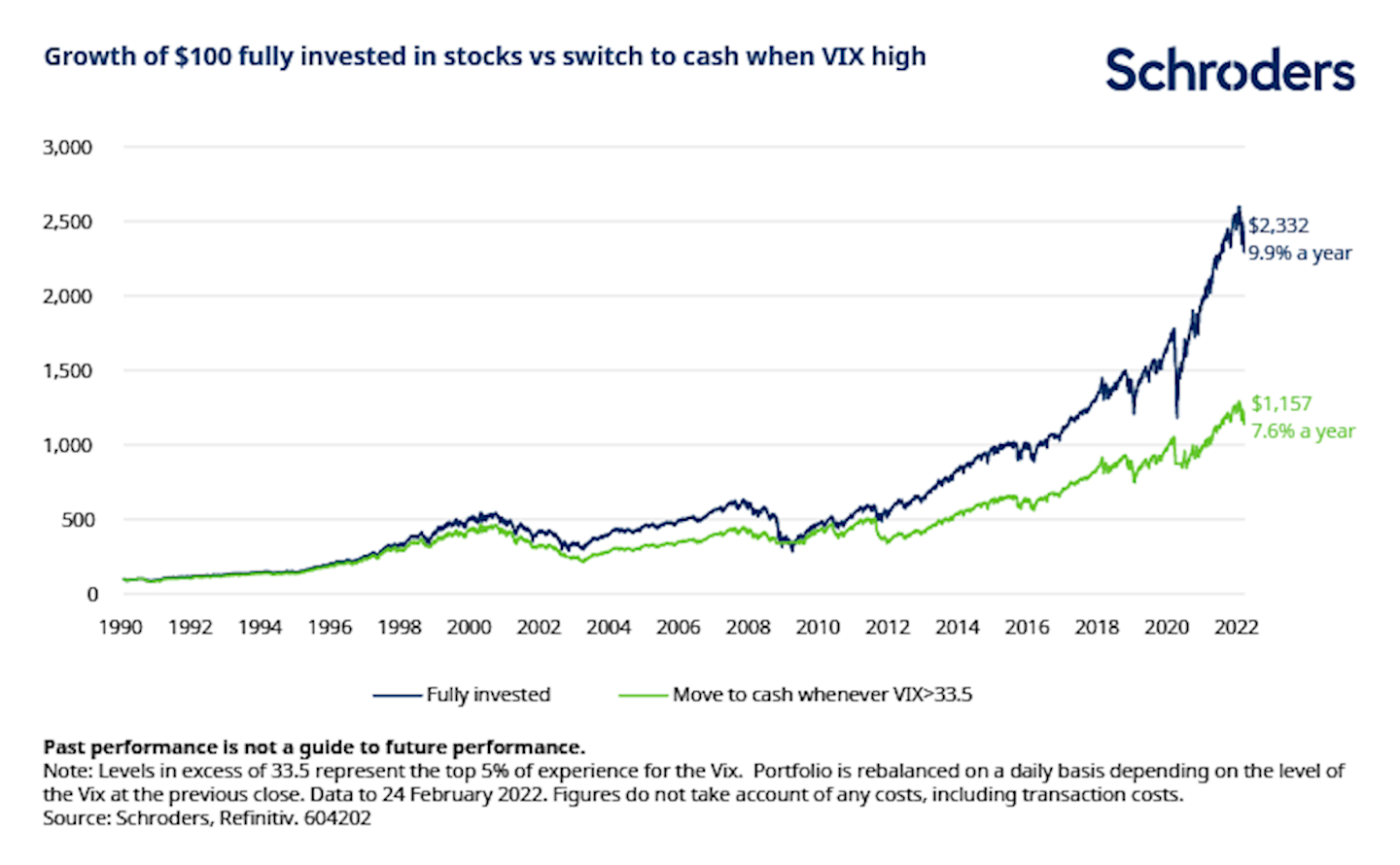

We also looked at a switching strategy, which sold out of stocks (S&P 500) and went into cash on a daily basis whenever the Vix entered this top bucket, then shifted back into stocks whenever it dipped back below. This approach would have underperformed a strategy which remained continually invested in stocks by 2.3% a year since 1991 (7.6% a year vs 9.9% a year, ignoring any costs).

A $100 investment in the continually invested portfolio in January 1990 would have grown to be worth twice as much as $100 invested in the switching portfolio.

As with all investment, the past is not necessarily a guide to the future but history suggests that periods of heightened fear, as we are experiencing at present, have been better for stock market investing than might have been expected.

Important information:

Marketing material for professional clients only. Investment involves risk. Any reference to sectors/countries/stocks/securities are for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument/securities or adopt any investment strategy. The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on any views or information in the material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Exchange rate changes may cause the value of investments to fall as well as rise. Schroders has expressed its own views and opinions in this document and these may change. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Insofar as liability under relevant laws cannot be excluded, no Schroders entity accepts any liability for any error or omission in this material or for any resulting loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise). This article may contain ‘forward-looking’ information, such as forecasts or projections. Please note that any such information is not a guarantee of any future performance and there is no assurance that any forecast or projection will be realised.

This material has not been reviewed by any regulator.