You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Article | 12 January 2022 | ESG

If you are struggling to keep up with all the ESG regulation that is emerging around the world, you are not alone. The volume of new rules may feel overwhelming or even intimidating. It helps to remember what they try to do: making sure that the investments we need to get our economies to a more sustainable place really happen.

In many cases, this starts from a country’s net zero emissions goal, which is going to be very expensive to achieve. At a time when governments face Covid-related mountains of public debt, the pressure falls on private investors. This is what ‘sustainable finance’ is about.

Policymakers have a long list of things on their agendas but invariably target three areas:

In this note, we provide a round up of the current state of play across the globe.

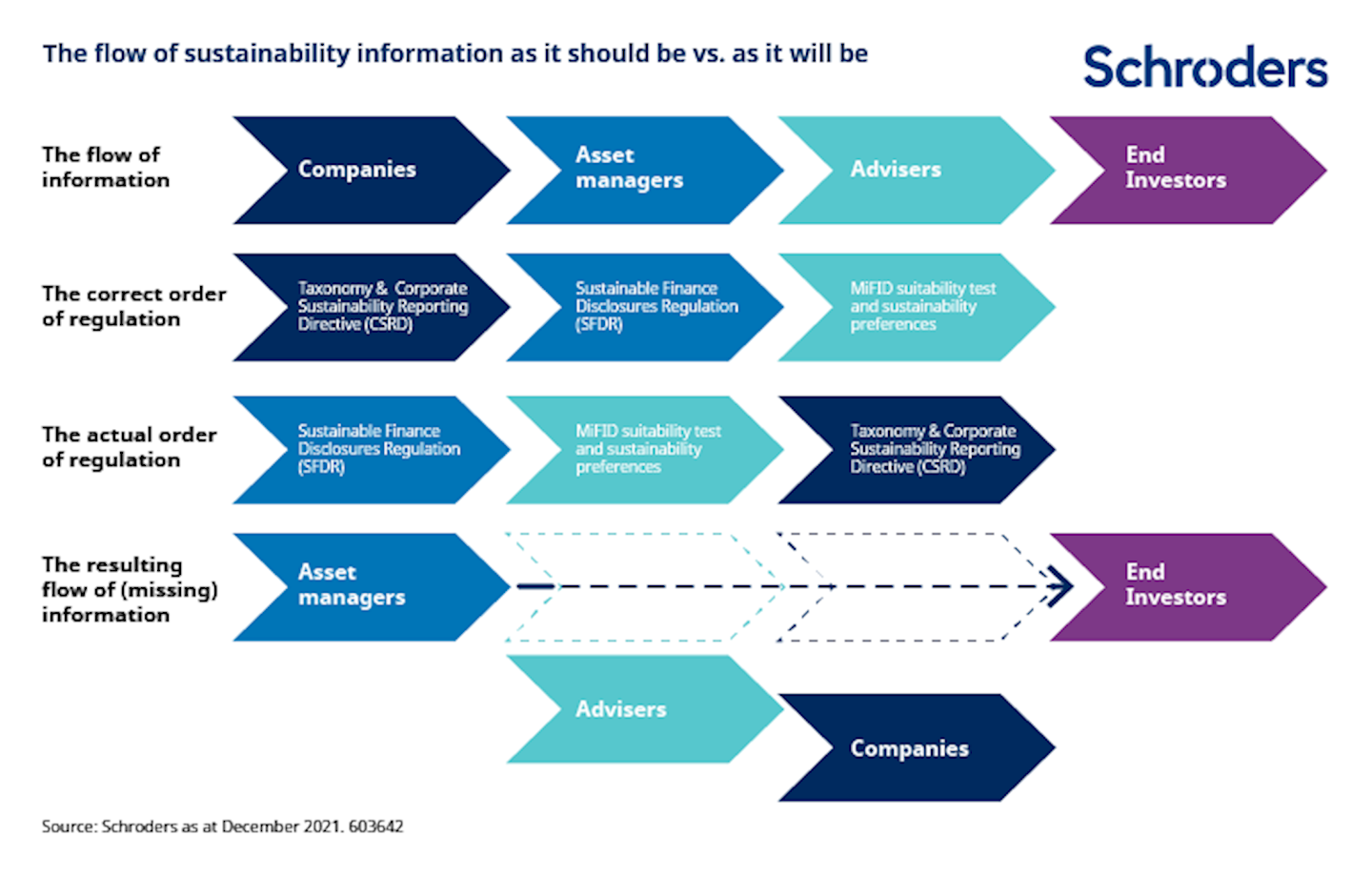

The European Union is getting most of the attention as it was the first region to develop a sustainable finance plan, largely based on disclosures and reporting. There is an EU Taxonomy to define what activities are considered sustainable. Companies use this to report on the sustainability of their activities as per the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Asset managers use this information to report on the sustainability of their products as per the Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR). Financial advisers then use this information for their discussions with end-investors to establish the latter’s ‘sustainability preferences’ as per the MiFID suitability test.

So you would be right to assume that this should be the order in which regulation is rolled out. Alas, the EU Taxonomy has been delayed for various reasons, including a hefty debate among member states on whether nuclear and gas will qualify as environmentally sustainable activities. Company reporting will not kick in before 2023. And the technical details on how asset managers report on the sustainability of their products won’t apply before 2023 either.

But as of January 2022, asset managers still have to show a number for their products’ alignment to an EU Taxonomy that is not complete, using company Taxonomy-alignment data that does not exist. And from August 2022, advisers are supposed to assess their clients’ preferences using the information that asset managers report, which is based on either incomplete or entirely missing data.

Another interesting complication is that some EU member states put their own extra touch or add new rules on top of the EU rules. We have seen this in France, Germany, Belgium, and Spain. Others may follow suit.

This partly ensues from an effort to interpret the EU rules in a way that makes oversight more straightforward given the continued delays and ongoing lack of clarity. Some of it relates to an attempt to distinguish (and perhaps protect) their respective domestic markets.

No matter what the reason is, the result is probably going to be the market fragmentation that the EU rules are trying to prevent.

The United Kingdom, in the meantime, has been rolling out mandatory reporting in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) across companies and financial services.

The principle is that with TCFD, the market can see where most carbon is emitted and allocate capital accordingly. But as sustainability is broader than climate change, the UK regulator has also unveiled plans for Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) that will effectively expand TCFD reporting to include (as yet undefined) sustainability factors.

In a way, it is the UK’s version of SFDR with the difference that SDR will also introduce labels for sustainable investment products; something that the EU policymakers have avoided on purpose. The details will be defined through a consultation process which will run over 2022. Of course, there are ongoing plans for a UK Taxonomy which will probably differ slightly from the EU one and for which more details will emerge over 2022.

The United States has seen a quite radical change in direction with the Biden administration, which has been pushing through new policies mostly focusing on climate change.

Hotly anticipated is the outcome of the review of Department of Labor (DOL) rules that came in January 2021 under the previous administration. In practice, these made it harder for private pension funds to invest in strategies with a sustainability angle and to vote on resolutions about environmental and social issues.

Under the new administration in March 2021, the DOL announced that it would not enforce the rules and, instead, consult with stakeholders. This culminated in new proposals released in October 2021 recognising that fiduciaries may consider sustainability factors when assessing investment opportunities and making proxy voting decisions.

The end result is expected in the first months of 2022 and, if it is similar to the proposal, it could unlock large pockets of capital for sustainable investment.

The markets in Asia have not been idle either. At the risk of oversimplification, most of the recent regulatory developments have been about improving corporate governance standards and company reporting.

We have seen this in Hong Kong’s revised Corporate Governance Code and listing rules that bring in, from January 2022, more stringent requirements for companies’ board independence and diversity as well as an earlier introduction of ESG reporting. Other examples are Taiwan’s plans to introduce more ESG disclosures in annual reports of listed companies and Singapore mandating company TCFD and board diversity disclosures in waves starting from 2022.

Another interesting characteristic in Asian markets is a strong focus on education. This has been apparent in Hong Kong Stock Exchange launching an ESG academy, which is a centralised educational platform for companies and the broader market. Meanwhile, Singapore is launching education workshops and e-learning platforms as part of its Green Finance Action Plan.

There is also a strong focus on bringing relevant information in one place. For example, the Korean Exchange has a dedicated segment for socially responsible bonds, in Hong Kong there is a publicly available database of sustainability funds on the regulator’s website while the regulator in Singapore has announced plans to pilot digital platforms for better sustainability data.

At the same time, China has been working with the EU on a ‘common ground taxonomy’ which has been launched through the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF). This is not a taxonomy per se but rather a tool that effectively compares the EU and Chinese green taxonomies and translates the one to the other. This is still under development but, if it works, it could be a very useful tool for those who invest globally.

Sustainable finance in Australia has been less about disclosures and more about managing climate change risk. Most of the recent regulatory activity has come from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) in the form of guidance for banks, insurers and pension funds on how to manage climate-related risks and opportunities.

The main concern in this respect is whether events relating to climate change can manifest as financial risks, for example, insurance companies being inundated with claims relating to extreme weather property damage. If this happens, it can mean trouble for insurance companies, which can then spill over to other financial market participants and destabilise markets more broadly.

There is some hope for company reporting. The launch of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is exactly about creating a global company reporting standard for sustainability metrics. The timings for delivery of those standards is somewhat uncertain but we remain very hopeful as national regulators such as in the UK have already signalled that they plan to endorse them.

Common standards for investment products are less likely. Some of the detail in the emerging UK framework is already different from the EU approach. We would not be surprised to see even greater differences compared to markets further away. That said, there is work by international regulators such as the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) which tries to bring some consistency to the way in which national regulators approach this.

So unless (or until) we get to a place of internationally accepted standards, we (and by that I mean everyone) will have to rely on a patchwork of different frameworks developed in each region.

You are probably wondering at this point who is doing this best and will, thus, ‘win’ the ESG regulation race. The answer is probably no one, for the simple reason that no one has done this before. We all have to climb a steep sustainability learning curve not knowing what is on the other side.

Important information:

Marketing material for professional clients only. Investment involves risk.

Any reference to sectors/countries/stocks/securities are for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument/securities or adopt any investment strategy.

The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations.

Reliance should not be placed on any views or information in the material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Exchange rate changes may cause the value of investments to fall as well as rise.

Schroders has expressed its own views and opinions in this document and these may change.

Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Insofar as liability under relevant laws cannot be excluded, no Schroders entity accepts any liability for any error or omission in this material or for any resulting loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise).

This article may contain ‘forward-looking’ information, such as forecasts or projections. Please note that any such information is not a guarantee of any future performance and there is no assurance that any forecast or projection will be realised.

This material has not been reviewed by any regulator.