You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Article | 10 September 2021 | ESG

Sustainability is everywhere. What used to be a niche topic is now part of our day-to-day business and personal discussions.

It is no wonder really: about two thirds of the global economy is attached to a net zero emissions goal while societies, partly prompted by the pandemic, are becoming increasingly aware of them.

The investment world is no exception.

Financial services regulators around the world are developing frameworks to encourage the flow of funds into sustainable investments. Assets managed with a sustainability tag have been increasing quite rapidly, reaching the $2 trillion mark for the first time in the first quarter of 2021, according to Morningstar.

According to the Schroders Institutional Investor Study[1], sustainability has become a prominent feature in conversations between asset managers and their institutional clients.

The 2020 edition of this study reported that almost half of institutional investors worldwide increased their allocation to sustainable investments in the previous five years (compared to just 1% who had decreased it), while almost 70% expected the role of sustainable investing to increase in the coming years.

The 2021 edition shows that this focus on sustainability is likely to accelerate further. More than half of investors globally believe the pandemic has made sustainable investing more important for their organisation.

So, as more and more countries unveil plans for sustainable finance, what could possibly stand in the way of sustainable investment becoming the norm?

The short answer is: lack of transparency. For the long answer, please continue reading.

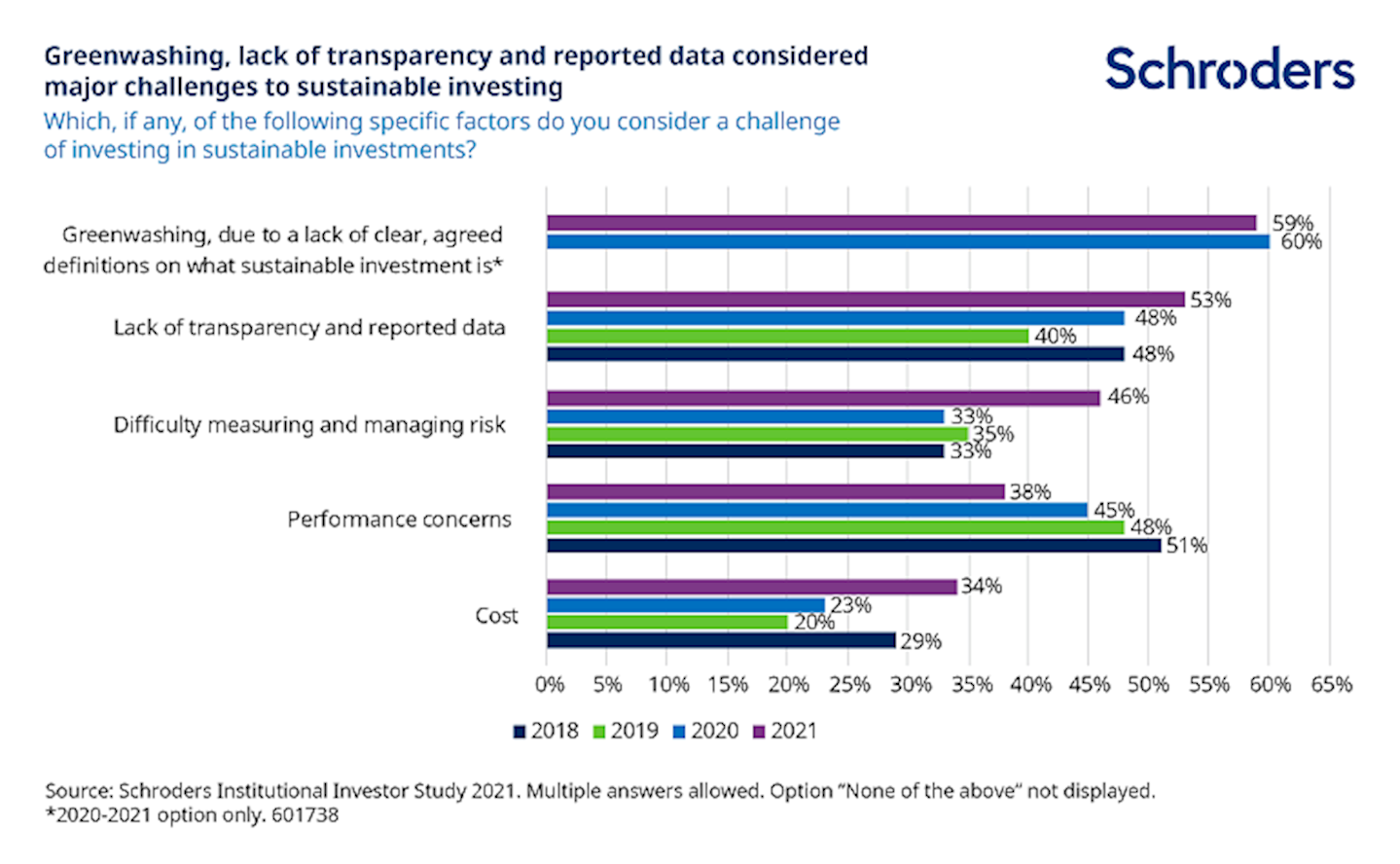

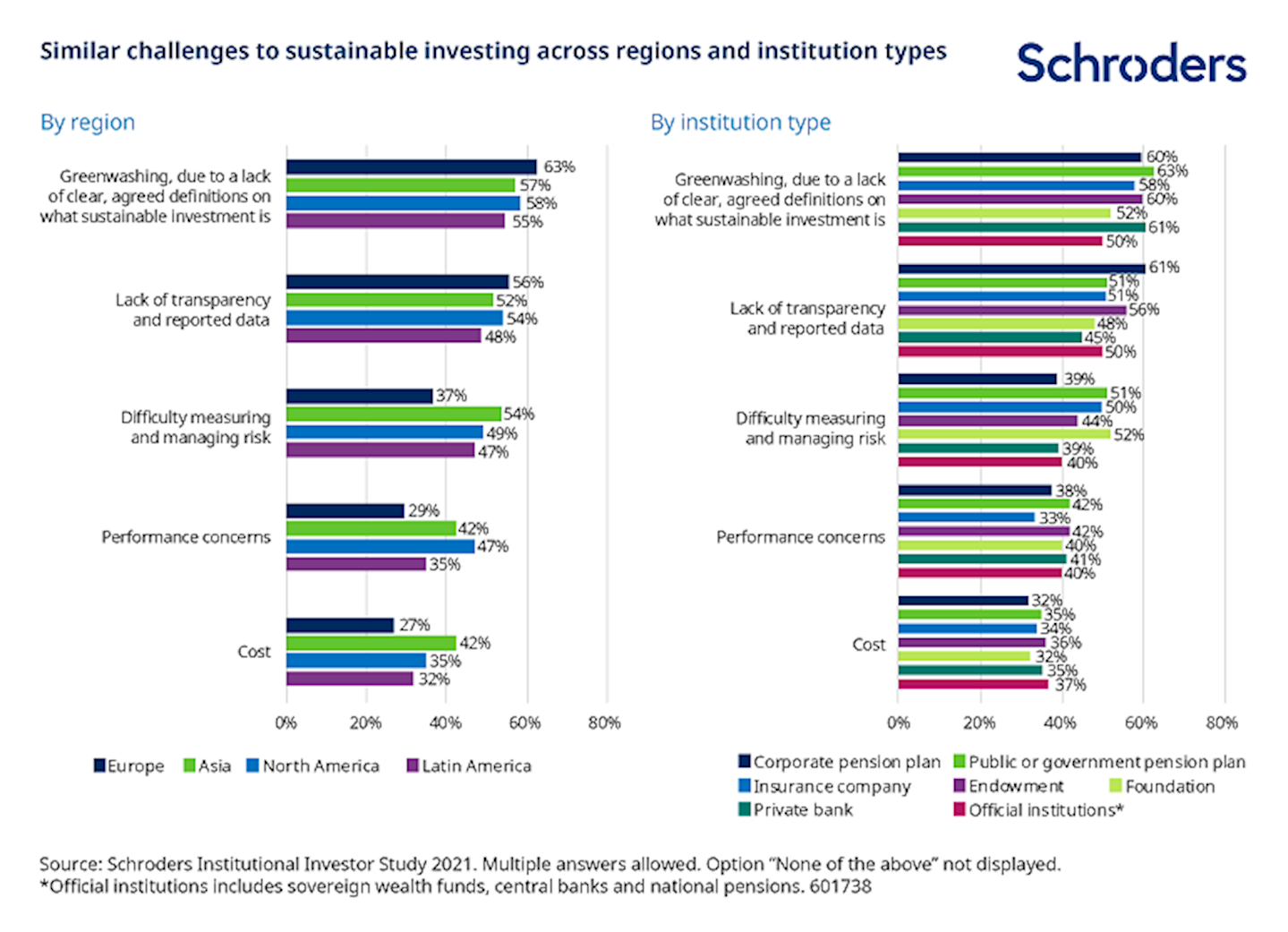

Generally, institutional investors across the world agree that the biggest barriers to making sustainable investments are concerns around greenwashing and a lack of common language and data on sustainability. In fact, the latter is probably one of the most consistent and long-standing findings of the Schroders Institutional Investor Study. It stands through the test of time (unfortunately) and is consistent both across regions and different institution types.

The challenges that investors flag are not independent from each other. As long as investors feel that there is not enough transparency and data, they will be worried about greenwashing. This can also spill over to how sustainability risks are identified and measured.

Unsurprisingly, regulators around the world are looking at the exact same thing: namely how to increase clarity and transparency around sustainable investment.

Looking at the different sustainable finance agendas that governments around the world are pursuing, it is clear that the most common building blocks are:

- a taxonomy classifying which economic activities are sustainable, and

- company reporting to ensure that the market gets the data around sustainability risk exposures, and how companies are tackling them.

We see this in the EU’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan, the taxonomy in China and the one being developed in Singapore, the sustainability fund disclosures guidance in Hong Kong, and the worldwide references to the Task Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework. Indeed, the TCFD requirements are now going to be mandatory in the UK and New Zealand and are recommended across many other markets such as the US, China and Singapore.

Having both a taxonomy and an adequate company reporting standard can then help with measuring, managing and disclosing sustainability risks on an investment portfolio level. It can also give investors a greater degree of confidence when allocating money towards what are reported to be more sustainable activities.

For more on global sustainability policies and regulation, please see How the world is warming to sustainable investing

Regulators and policymakers are making transparency the number one priority for sustainable finance as (similar to investors) they see lack of common understanding and data as a potential barrier to further growth in the market.

Greenwashing is a risk as some activities unjustly position themselves as sustainable and attract money intended for sustainable purposes, when the reality is quite different. This leaves less money for those activities which can create a more sustainable economic system and it severely harms confidence in sustainable investing. This is bad news for everyone.

But blacklisting everything that is not on a taxonomy's "green list" has a risk too. It could see investments that contribute to social and governance goals, not being branded as "green", thus receiving less funding from the market than they otherwise would.

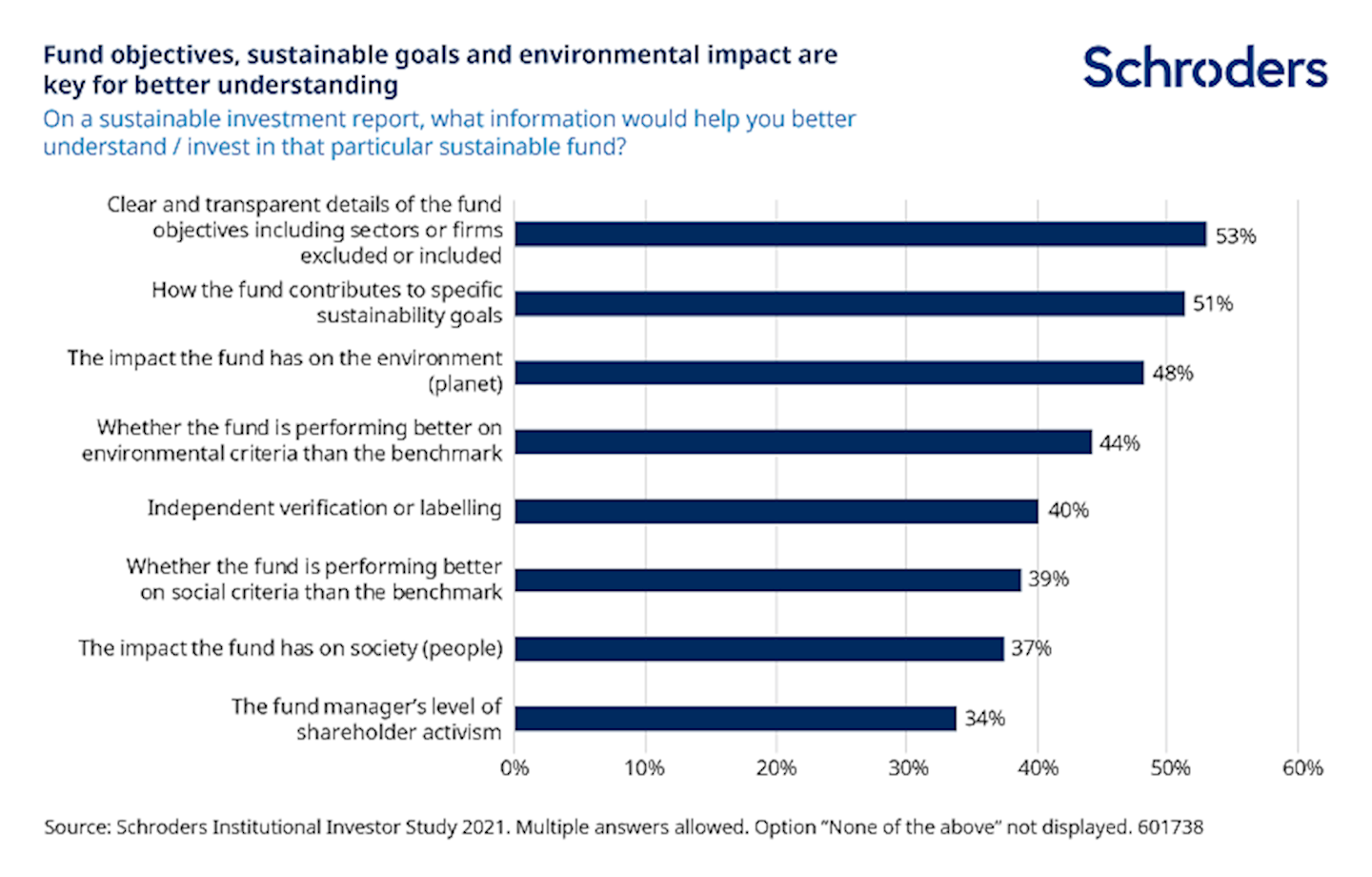

Institutional investors have explicitly flagged what type of information would be most useful for their understanding, from more details on fund objectives to the impact a fund has on sustainability goals and the environment.

Since regulation seems to be addressing the areas that investors want to be addressed, the question is: will it work? Will all the additional transparency result in more money flowing towards sustainable investments?

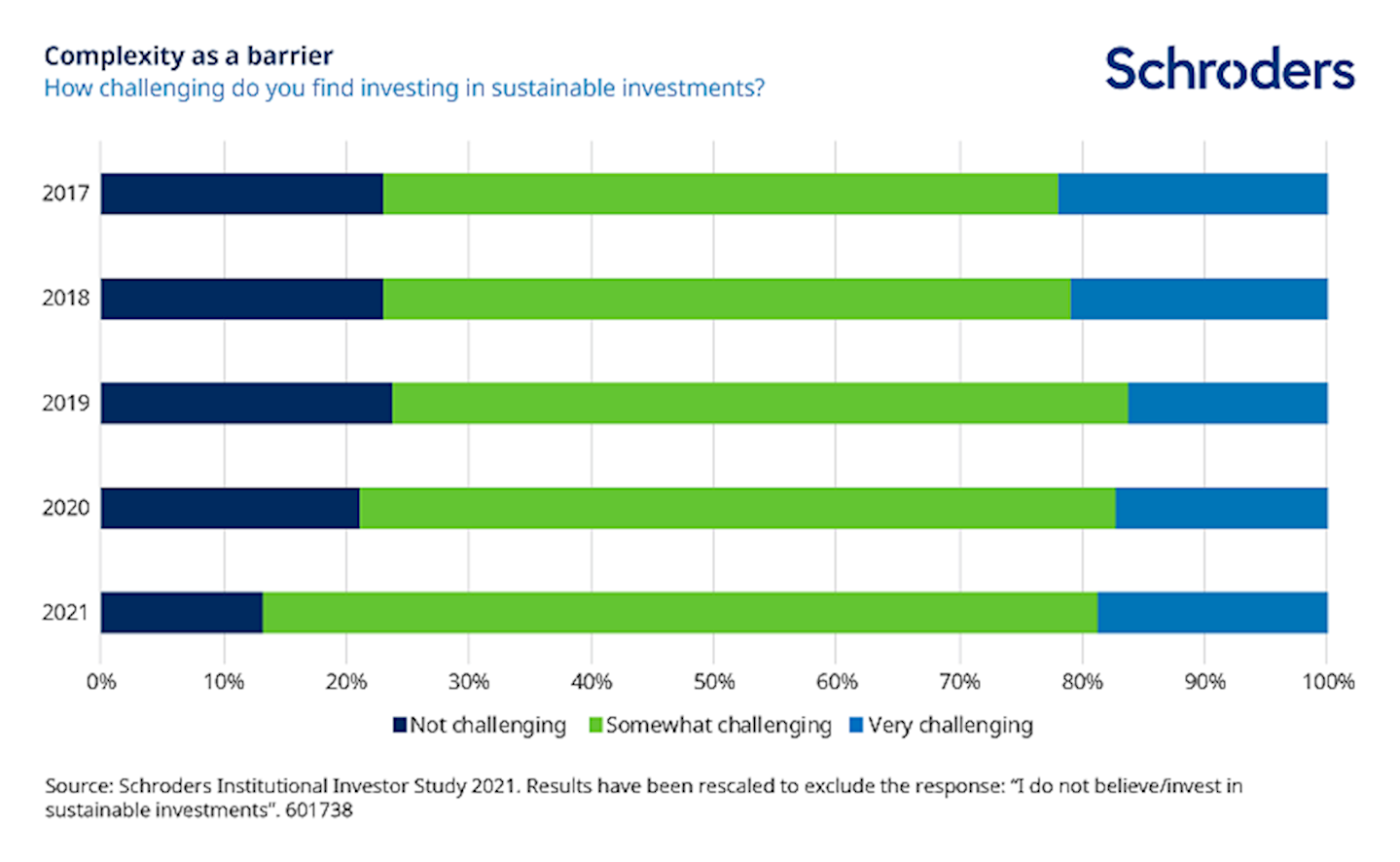

Despite all the new regulation intending to improve transparency, according to our 2021 Institutional Investor Study, a large proportion of investors still think that sustainable investing is challenging.

In fact, through the years the proportion of investors who do not find it challenging is shrinking, which indicates that sustainable investing suffers from a stubbornly high degree of complexity.

Measuring and understanding social and environmental issues through an investment lens is still very new to many investors. If we see this in combination with the lack of consistency in definitions, data and methodologies, it should not be surprising that so many still find sustainable investing at least somewhat challenging.

Hence, there is still a lot of work to do to make investors feel confident that they have all the tools and information to make informed decisions. Which probably means that neither the industry nor regulators have found the silver bullet yet.

This could be the result of a number of things.

For one, the regulation and all the policies being developed are still “work in progress”. Some have been developed at great speed in a rapidly developing market and there has not been enough time for them to bed in or be fully understood. They may not always have been developed in a logical order. This, in turn, means that it will probably take some more time for us to see all the disclosures and to be able to assess whether they have made a difference.

Another possibility is that the market needs more investor engagement and empowerment. It is one thing for all the data to be there and a different thing for investors to know how to interpret and use it. In fact, building knowledge and capability around sustainable finance is part of several action plans, such as the ones in Canada, Singapore and New Zealand.

While both are possible, it may well be that the real reason lies elsewhere.

More data and reporting are necessary but they are not sufficient to increase sustainable investment. It is like expecting that showing how many calories, fat, salt and carbohydrates each item of food has will be enough for people to lose weight.

It is necessary for people to know what it is they are eating and what is most likely to result in an expanding waistline. But it is not enough. They need to actively choose to act upon this information. To do so, they might need nudges to make it easier for them. As Richard Thaler, the renowned behavioural economist, once said: “If you want people to do something, make it easy”.

This is why disclosure alone is not enough. This is where incentives come in.

Of course, investing is not an every-day decision in the same way buying food is, but the premise is similar. It is becoming apparent that we need more action to make sustainable investments an attractive proposition.

The European Sustainable Investment Forum (EuroSIF) recently outlined that the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation cannot promote sustainable investment on its own, even if it helps create a common language around environmental sustainability.

The main reason is that about half of the investments needed for the EU’s transition to a net zero emissions future are not going to produce positive investment returns without very targeted policy interventions, according to a McKinsey report. For example, without adequate carbon pricing to reflect carbon’s very real negative effects on the environment, carbon remains a cheaper and more profitable choice.

Transparency and reporting are needed to enable sustainable investment, but they are no guarantee that this investment will take place. For this, the market needs industrial policy that will make sure that the investments needed for a more sustainable economy make for a good investment proposition.

And by that I mean not only the activities that are already sustainable, but also those that need to transition from non-sustainable to sustainable.

Important information:

Marketing material for professional clients only. Investment involves risk. Any reference to sectors/countries/stocks/securities are for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument/securities or adopt any investment strategy. The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on any views or information in the material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Exchange rate changes may cause the value of investments to fall as well as rise. Schroders has expressed its own views and opinions in this document and these may change. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Insofar as liability under relevant laws cannot be excluded, no Schroders entity accepts any liability for any error or omission in this material or for any resulting loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise). This article may contain ‘forward-looking’ information, such as forecasts or projections. Please note that any such information is not a guarantee of any future performance and there is no assurance that any forecast or projection will be realised. This material has not been reviewed by any regulator.